Writing The Long Goodbye

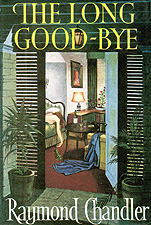

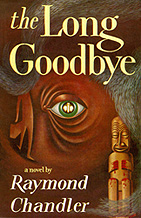

When Bruce Taylor owned the San Francisco Mystery Bookstore, he had a table of featured books in a central location. The books on the table changed from time to time to highlight currently popular releases or books that Bruce had read recently and enjoyed. But one book was never removed: Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye. And beneath the stack of continuously restocked copies was a hand-written note that read, “Best Book in the Store.”

While I personally believe that the best book in the store had to be one of Chandler’s, some fans of the writer might make a case for a different selection. There’s a certain primeval power to any first novel and Chandler’s The Big Sleep had it in spades. Another contender would be Farewell My Lovely, which had more mature writing than Sleep–most notably a more even-handed application of Chandler’s famous similes–an amazing collection of well-drawn characters (Moose Malloy, Jesse Florian, Second Planting, Jules Amthor and “Hemingway” to name a few) and one of the more satisfying and less obtuse plots of all the books.

But even if you select another book as Chandler’s best, perhaps because you simply find them more entertaining, there’s little question that The Long Goodbye was Chandler’s most ambitious book, the book where he attempted to stretch the boundaries of private eye fiction to take the genre into the realm of serious literature. Bruce Taylor would tell you that he succeeded–and so would I.

Yet The Long Goodbye was written under extraordinarily difficult circumstances and underwent a major rewrite after Chandler submitted what he expected to be the final draft to his agents in 1952. I recently had the opportunity to examine some 200 pages of original typescript with excised or rewritten scenes while visiting the special collection of Raymond Chandler papers at the Bodleian Library at Oxford University. From this visit, I gleaned new insights about Chandler’s unusual writing process and discovered some of the fairly substantial–and surprising–changes he made to the plot in the process of creating the published version of the book.

Background

While every writer struggles over a manuscript to some extent, the extra challenge Chandler faced while writing The Long Goodbye was a particularly grim and poignant one: his wife Cissy was dying. Cissy was almost 18 years older than Chandler and by the time he started the book in 1949, she was nearly 80 and was troubled by a debilitating lung condition, which, while never cleanly diagnosed, was probably a form of emphysema. The disease left Cissy weak and often bed-ridden and Chandler could see the inevitable end. It depressed him terribly. He wrote to his English publisher, Hamish Hamilton, “In bad moods, which are not too infrequent, I feel the icy touch of despair. It is no mood in which to produce writing with any lift and vitality.”

Nonetheless, he worked on the novel in fits and starts through May 1952, when he submitted the book to his agent Bernice Baumgarten at the New York firm of Brandt and Brandt. Chandler was confident enough that the book was ready for publication that he wrote Hamilton to tell him he would soon be receiving a copy. But when Baumgarten and Carl Brandt, the head of the agency, read the manuscript they felt that there were problems with the character of Chandler’s PI, Philip Marlowe.

In his effort to write a “serious” novel, Chandler had put more focus on Marlowe than ever before, and in trying to illustrate the importance Marlowe places on his friendship with Terry Lennox–and his ultimate disillusionment with Lennox in what Marlowe sees as his moral bankruptcy–Baumgarten and Brandt concluded that Marlowe had become too soft and sentimental. Baumgarten wrote in a letter to Chandler, “We feel that Marlowe would suspect his own softness all the way through and deride it and himself constantly.”

The original version of the manuscript is not available in the Oxford collection, but by all accounts, the observation was an accurate one. Chandler admitted that his mood and concern over his wife may have influenced the writing and agreed to do a revision. He also decided to change the ending of the book. However, the critique by Baumgarten and Brandt had not been delivered with the greatest sensitivity, and Chandler felt stung by the criticism. He ended up breaking with Brandt and Brandt before the book’s publication.

With some interruptions–including a trip to England–Chandler worked on revisions throughout the remainder of 1952 and into 1953. The manuscript pages in the Oxford collection are byproducts of these rewrites, but do not reflect the final text in the book. They represent versions of scenes that were done differently in the finished novel and a few short scenes that were omitted entirely. In movie parlance, they would be “alternative takes” or scenes that were left on the cutting room floor.

Chandler’s Writing Process

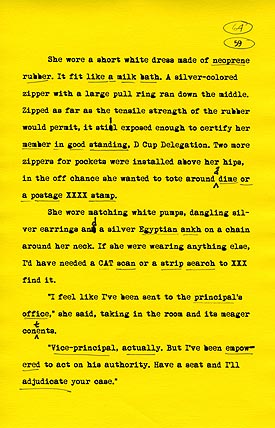

The first thing that struck me when I opened the boxes containing the manuscript pages at Bodleian Library was their unusual form. Chandler composed his novels on a typewriter, but instead of using American letter-sized paper, he used yellow half sheets, oriented 5.5 inches in width and 8.5 inches in length like a small portrait page. The rationale for this was to limit the amount of retyping required if Chandler elected to rewrite something on a page.

Of course word processors have automated much of the (physical) drudgery of revising, but I thought this was a unique mid-twentieth century solution for reducing the workload. And, as I describe later, it was particularly handy for Chandler given his unconventional approach to rewriting.

In addition to the manuscript page size, I found the notations and the markings on the sheets interesting. I’d hoped to be able to reproduce a representative sheet of the manuscript to illustrate, but copying or reproducing material beyond “fair use” requires approval from the Chandler estate and I wasn’t able to secure it. In lieu of that, I’ve typed out a short section from one of my own books and annotated the page with the sort of markings that are present on the pages from The Long Goodbye.

As you’ll see in the “mock-up,” Chandler corrected typos either by XXX’ing them or by hand in ink. However, he almost never made substantive revisions by hand, presumably preferring to retype the page. Page numbers were typed in the upper right hand corner–often circled in pencil. In addition, another page number in pencil (circled) was often shown above the typewritten one. I believe the typewritten number was the original number of the page when first written by Chandler. I suspect the number in pencil was the position the page held after revisions, shuffling of scenes, etc. The circling of the numbers might have been a “flag” that the page had been through a review cycle and was okay to be included in the draft Chandler was currently working on.

As you’ll see in the “mock-up,” Chandler corrected typos either by XXX’ing them or by hand in ink. However, he almost never made substantive revisions by hand, presumably preferring to retype the page. Page numbers were typed in the upper right hand corner–often circled in pencil. In addition, another page number in pencil (circled) was often shown above the typewritten one. I believe the typewritten number was the original number of the page when first written by Chandler. I suspect the number in pencil was the position the page held after revisions, shuffling of scenes, etc. The circling of the numbers might have been a “flag” that the page had been through a review cycle and was okay to be included in the draft Chandler was currently working on.

Those details are fairly prosaic perhaps, but the final type of markings on the page is quite a bit more interesting. Chandler made pencil underlines beneath various phrases and words in the text. These puzzled me until I compared the versions of particular scenes in the manuscript with the final version of the scene in the book. What I found is that those words were the only thing in common between the draft version and the final version.

Chandler’s method of rewriting was radical. Rather than keeping most of what was in his current draft and making accretive changes to it, he started nearly from scratch, saving only the few words or phrases that resonated from the previous draft. Returning to the movie making metaphor, Chandler’s rewrites were truly more akin to alternative takes where the director encouraged the actors to take a different line through the scene. Here’s a small sample of text from the Oxford manuscripts from the scene where Marlowe confronts Roger Wade about some stream-of-consciousness writing he’s typed while he was drunk. I’ve reproduced Chandler’s strike-throughs and pencil underlines as they are on the manuscript:

I stood up and reached

thefolded yellow sheetsfrom his typewriterfrom my breast pocket and handed them across the desk. “You wrote this when you were drunk and left it on your typewriter. Under the cover. Upstairs you asked me to tear it up so Eileen wouldn’t see it. You’d better read it over.”

Here’s how the same fragment appears in the final U.S. published version:

I got up and handed him some folded yellow sheets. “You’d better read it. Evidently you don’t remember asking me to tear it up. It was in your typewriter, under the cover.”

You can see that the underlined sections are preserved almost word-for-word in the published version. This example is not the best in terms of showing the breadth of rewriting that Chandler undertook because the meaning and tone is the same between the two drafts, and only represents a tightening up of the narrative. Other scenes in the Oxford manuscripts are intriguingly different, as I discuss below.

As an aside, it’s interesting to note that Chandler has author Wade typing his manuscripts on yellow paper. He doesn’t go so far as to have him use half sheets, but they are folded. Many critics have said that Wade provided an opportunity for Chandler to give voice to his own thoughts about writing–and his life in general. One quality that Wade has which Chandler apparently didn’t was the ability to type clearly without corrections while drunk. The manuscript pages at Oxford are typed in a workmanlike fashion, but there are a number of typos. Unless Chandler’s proficiency improved markedly when he drank, it appears that Wade, at least, was the better typist.

The Long Goodbye that Might Have Been

There are two sets of manuscript pages for The Long Goodbye at the Bodleian Library. The first is dated June 24, 1953 and the second is dated July 9, 1953. The first set is at least half again as long as the second and includes pages with alternate versions of these scenes in the published version of the novel:

- The showdown with Eileen Wade, which is described in chapters 42 and 43 of the U.S. edition

- The confrontation with Mendy Menendez at Marlowe’s Laurel Canyon house, which is described in chapters 47 and 48

- The closing scene between Marlowe and Terry Lennox, aka Cisco Maioranos, aka Paul Marston, described in chapters 52 and 53

The July 9th set of pages has alternate versions of these scenes:

- The meeting between Wade and Marlowe when Marlowe comes to the house for lunch, described in chapter 34

- The confrontation with Mendy Menendez (as above)

- The closing scene (as above)

Cuts

I’ll describe the alternative “takes” below, but there are also a few short scenes that were cut entirely from the published book. The first, from the June 24th pages, has Marlowe going back out to Idle Valley after Eileen Wade is dead. He notices the hibiscus that grows along the fence at the edge of the property has been severely cut back. Then he watches as a woman comes out of the house, gets a car out of the garage and proceeds to stall it in the driveway. In the course of helping the woman start the car–which is flooded–Marlowe engages her in conversation. He tells her that he knew the people who owned the house before her. She says that she understands someone died there, but that she doesn’t care because she and her husband got a better deal as a result.

The scene doesn’t serve any real purpose except to underline how little impact the Wades’ passing has had on the world and it’s easy to see why Chandler cut it.

Another excised scene the July 9th pages is a curious one that takes place just before the final Mendy Menendez meeting. Marlowe meets a well-dressed man while walking back home from dropping off his car at a garage to have his brakes checked. The man asks for a match to light his cigar and then asks for a dollar to pay for a cab back to his hotel.

The man justifies the cab by explaining that he’s been out for a long walk, but says that he can’t go back through Beverly Hills because the Beverly Hills police stop pedestrians at night. Marlowe gives him the dollar after pointing out that the hotel would pay the cab for him. The man then asks for his address to return the dollar and Marlowe hands him his card saying, “I’d rather you wouldn’t return it, though. It’s the best gag I’ve heard all week.” The man is a little taken aback and says that he hopes Marlowe doesn’t think he’s a panhandler. Marlowe responds by doing a sort of Sherlock Holmes analysis on him, examining his clothes and his jewelry to determine that he’s a well-to-do gentleman from Philadelphia by the name of “Drexel Curtis Biddle.”

This scene, too, is extraneous, but is a rather humorous one, and given the description of the well-dressed “panhandler,” I wondered if the man was supposed to be Chandler himself.

Other “Takes”

Reviewing the alternate scenes in the same sequence as they appear in the published book, the first one would be the lunch scene between Marlowe and Roger Wade from the July 9th pages. One interesting difference in this scene is the amount of “air time” Chandler gives to the topic of writing. In this version, Wade gives Marlowe an extended lecture on the topic. He explains that hack writers often deploy a mechanical hook to start a story, and goes on to give a specific example of what he means: “When the fourth shot came I already knew who the murderer was in the same breath I knew that only by a miracle would I ever be able to prove it.” A talented writer would never do this, he says, because by jerking the reader into the middle of the plot before he knows anything about the characters, he throws away the chance to interest the reader in the characters as people.

This provides good insight into Chandler’s philosophy as a writer, but probably strains credibility to have Wade discussing these finer points with Marlowe. Another interesting difference is the story Wade tells Marlowe about Sylvia Lennox tricking Dr. Loring into her cottage, pulling a gun on him and chasing a naked Loring out of the cottage. This has the effect of throwing suspicion onto Dr. Loring, and is of course very ironic since Loring is portrayed as prig who is very jealous of other men’s attention to his wife Linda.

Showdown with Eileen Wade

The version of the showdown with Eileen Wade in the June 24th pages is surprisingly different from the published version. Howard Spencer and Candy take a much more active role in confronting Eileen about the death of Sylvia Lennox and Roger Wade, and it is Spencer who actually accuses her of killing Roger. At that point, she runs upstairs to her bedroom and Marlowe takes the opportunity to call Bernie Ohls. Spencer and Marlowe remain in the living room discussing Eileen’s motives for the killings and eventually Ohls shows up.

Then Eileen comes back down the stairs carrying a gun, which she pulls on Ohls. She says that she hates all men, except one who is dead (Paul Marston) and takes a shot at Ohls. She misses. She turns the gun on herself and shoots herself through the heart.

I found this scene much less nuanced than the published version, and was surprised at the relatively passive role Marlowe has in it. Unquestionably, the published version is a big improvement. It’s more realistic to have Spenser and Candy drawn over to Marlowe’s way of thinking gradually, and the manner in which Marlowe tricks Eileen about the fence around the reservoir makes a more subtle and clever dénouement than the outright accusation Spencer makes. Also, Ohls appearance on the scene is too convenient and only serves to lessen Marlowe’s stature.

Mendy Comes Calling

There are two alternative versions of the confrontation with Mendy Menendez: one in the June 24th pages and another in the July 9th. Surprisingly, in both versions Mendy actually makes an appointment to meet with Marlowe at his house (rather than ambushing him unexpectedly at the door), and in the July 9th version, Randy Starr is also present.

The June 24th version is more violent and Marlowe evidences more concern about the risk to his person before the meeting, checking all his guns and going so far as to search his car for a bomb. And when Menendez does show up, Marlowe actually pulls his gun and fires several rounds into the limousine before being drawn inside the house.

The July 9th version is more sedate, with Starr quizzing Marlowe on the reasons for his involvement, speculating that someone “has paid him off.”

Both alternatives again seem less nuanced than the published version and I think the scene benefited from the final rewrite.

The Final Goodbye

The most interesting aspect of the alternative takes for the final scene between Marlowe and Terry Lennox is the apparent difficulty Chandler had in coming up with closing lines of the novel.

In the June 24th pages, the novel ends with these lines (I’ve included Chandler’s strike-throughs as they appear on the manuscript):

He turned quickly and walked out. I watched the door close. I listened to his steps going along the hall.

They died.Then I just listened.

Slow curtain.

This is too abrupt and conveys little of the emotion Marlowe has to feel in rejecting his former friend, but Chandler may have written it this way in response to Baumgarten and Brandt’s criticism about Marlowe’s apparent softness and sentimentalism.

The July 9th pages have two versions of the ending. Here is the first:

He turned away quickly and went out. I watched the door close and listened to his steps going away. After a little while I couldn’t hear them, but I kept on listening.

Don’t ask me why. I couldn’t tell you.

The second version of the lines in the July 9th pages were done by amending the manuscript in pen, which as I mentioned earlier, was unusual for Chandler: he usually retyped the page. This is probably further indication of the struggle he was having in hitting the right tone and mood.

He turned and went out. I watched the door close and listened to his steps going away. Then I couldn’t hear them, but I kept on listening anyway. As if he might come back to talk me out of it. As if I hoped he would.

But he didn’t.

After rereading this, Chandler must have felt he had overcompensated. The final sentence, “But he didn’t” almost comes across with a catch in the throat. Here’s how he handled it in the published version of the novel:

He turned and walked across the floor and out. I watched the door close. I listened to his steps going away down the imitation marble corridor. After a while they got faint, then they got silent. I kept on listening anyway. What for? Did I want him to stop suddenly and turn and come back and talk me out of the way I felt? Well, he didn’t. That was the last I saw of him.

I never saw any of them again—except the cops. No way has yet been invented to say goodbye to them.

This version isn’t rushed—the extra description slows the narrative and adds weight to what is occurring. It also manages to convey an appropriate depth of feeling at the parting, while at the same time retaining Marlowe’s cynical worldview.

The published version succeeds so well, in fact, that American Book Review ranked the last sentence #62 in its compilation “100 Best Last Lines from Novels.”

Publication and Reception

The Long Goodbye was published in England by Hamish Hamilton in November 1953 and in the United States by Houghton Mifflin in March 1954. As was true with much of Chandler’s work, the initial critical reception in England was stronger than it was in the U.S. Many in England immediately regarded the work as Chandler’s best and the Sunday Times reviewed him as a novelist, rather than a detective storywriter, which pleased Chandler very much.

The Long Goodbye was published in England by Hamish Hamilton in November 1953 and in the United States by Houghton Mifflin in March 1954. As was true with much of Chandler’s work, the initial critical reception in England was stronger than it was in the U.S. Many in England immediately regarded the work as Chandler’s best and the Sunday Times reviewed him as a novelist, rather than a detective storywriter, which pleased Chandler very much.

On this side of the Atlantic, the New York Times published two reviews. The first, written by Charles Poore on April 8, 1954, hailed the book as the “old master’s masterpiece.” The second, written by Anthony Boucher (of Bouchercon fame), came out on April 25th. It is especially interesting because Boucher was no fan of Chandler, having previously damned his The Little Sister for its “scathing hatred of the human race.”

Yet even Boucher saw something different about The Long Goodbye. “It’s a moody, brooding book, in which Marlowe is less a detective than a disturbed man of 42 on a quest for some evidence of truth and humanity.” He closes with, “Perhaps the longest private-eye novel ever written (over 125,000 words!). It is also one of the best–and may well attract readers who normally shun even the leaders in the field.”

Reviews like this from Boucher were only the start because over time critics on both sides of the Atlantic came to recognize The Long Goodbye as a novel that truly broke through the boundaries of genre fiction into literature, and many echoed the evaluation of the novel as Chandler’s best. Novelist and critic Anthony Burgess included it as his only selection for 1954 in his list, “99 Novels: The Best in English Since 1939.” This is a list populated with the likes of Finnegan’s Wake, Nineteen Eighty-Four, The Catcher in the Rye and Catch-22, with only a smattering of other entries that might be categorized as genre.

Finally, it must be said that the book was recognized by those who continued to toil in the genre Chandler had worked so hard to break free of: it was also awarded the Edgar for best novel in 1955, the same year that Agatha Christie was elected as the Mystery Writers of America’s first Grandmaster.

Finally, it must be said that the book was recognized by those who continued to toil in the genre Chandler had worked so hard to break free of: it was also awarded the Edgar for best novel in 1955, the same year that Agatha Christie was elected as the Mystery Writers of America’s first Grandmaster.

Notes and Acknowledgements

All quotes from Chandler’s and his agents’ letters are taken from The Life of Raymond Chandler by Frank MacShane. Likewise, much of the biographic material in the article comes from the same source, and it should be noted that MacShane also gives an analysis of the closing lines of The Long Goodbye in his chapter on the novel. However, he doesn’t quote the first version of the lines that I found in the June 24th pages, and he deciphered the wording of the subsequent two versions from the July 9th papers a little differently than me.

I also used Raymond Chandler: A Biography by Tom Hiney for biographic information, and relied on my trusty 1973 printing of the Ballantine Books edition of The Long Goodbye for all quotes from the published version of the book (not wanting to handle my US and UK first editions more than necessary!).

I would like to thank Bill Mullins for locating and forwarding the Charles Poore review, and Colin Harris of the Department of Special Collections of the New Bodleian Library at Oxford for all his thoughtful assistance in securing access to the papers and doing the research.

Further Reading

Mark Coggins is the award-winning author of eight novels featuring private eye August Riordan. If you enjoyed The Long Goodbye, you may like his latest effort, Geisha Confiential, which is a “very well written PI story set in modern Tokyo… in the proud tradition of Chandler, Hammett, Runyon, and the rest, though none of their femmes (fatale or otherwise) were like Coco, depicted in this story,” according to Nonstop Reader.